Forest ThreatNet

Branching Out

NCSU Researcher Examines Forest Genetics and Evolution

By Stephanie Worley Firley, EFETAC and Karin Lichtenstein, NEMAC

What causes someone to make a drastic career change from newspaper journalism to forestry research? Curiosity—and a love of writing, of course.

Above right: NCSU researcher Kevin Potter performs forest genetics research in a fir forest.

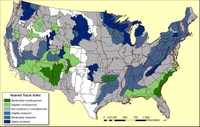

As a cooperator with EFETAC’s Forest Health Monitoring (FHM) team, Potter has used information from dozens of recent plant gene sequencing studies to construct an evolutionary "tree of life" that shows how 311 tree species may be related. "Evolutionary diversity is the cumulative evolutionary history of a group of organisms. It may tell you something about a community’s resilience in response to threats, such as pests and climate change. Trees in a community that are more clustered on the tree of life are more closely related and may be more susceptible to certain forest threats," says Potter. Maps from Potter’s research revealed this clustering among forest tree communities in the Appalachians, Upper Midwest, and Pacific Northwest. According to Potter, these areas may be at greater risk of generalist pests and pathogens because of this clustering. On the other hand, some ecoregions in the Interior West and along the Southeastern Coastal Plain appear to be over-dispersed, meaning that the species tend to be less closely related; therefore, the communities may be less at risk.

Species richness, or the number of tree species present in a plant community, does not always correlate with evolutionary diversity. For example, Potter’s examination of Forest Inventory and Analysis tree data shows that evolutionary diversity is higher than species richness in some ecoregions, including in New England and the Pacific Northwest.

Species richness, or the number of tree species present in a plant community, does not always correlate with evolutionary diversity. For example, Potter’s examination of Forest Inventory and Analysis tree data shows that evolutionary diversity is higher than species richness in some ecoregions, including in New England and the Pacific Northwest.

Above: Map shows that sections with significant phylogenetic (evolutionary history) overdispersion (green) are confined to the Interior West and the Southeast. Sections with the greatest clustering (blue) are in the Upper Midwest and the Great Plains. Phylogenetically overdispersed communities are expected to be more genetically resilient to change.

Potter believes this kind of research may change the way natural resource managers pursue conservation efforts. "We may do a better job conserving the biodiversity of an area by targeting the evolutionary diversity of forest tree communities than by focusing on species richness. This is an approach that conservation biologists have been using in Australia and Europe recently, and in some global assessments of mammal biodiversity. I think it has some potential to be useful in the United States as well," says Potter.

With support from Frank Koch and Mark Ambrose, NCSU colleagues as well as EFETAC cooperators, and Kurt Riitters, FHM landscape ecologist, Potter is writing about his findings and thinking about his future work involving forest genetics. "I plan to assess whether invasive plant species are more likely than not to share a common recent evolutionary history (compared to non-native plant species that don’t become invasive, for example), and attempt to use the evolutionary relationships among host species to generate maps of pest and pathogen risk," he says. "In general, I think it’s important to consider evolutionary biology when thinking about forest threat issues, since evolutionary forces play a central role in shaping processes and patterns in the natural world."

« Previous page Next page » Return to contents